I cannot forget the last twenty sixty minutes of this film. They are burned into the whites of my eyes, escaping the black hole of the iris. As if I was reading Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking for the first time, again I became a witness to the atrocities committed against the Chinese during the Sino-Japanese war; conventionally known in Amerikka as the Pacific Front of World War II. The scene, a wholesale and indiscriminate massacre of Chinese denizens in Rack-Armor Terrace by the occupying Japanese forces evoked a rage that shook me to the core. Still, I had to ask, was I even entitled to it? Entitled to a historical legacy that continues to this day, found in the continued denials by the Japanese government that anything happened? I cannot rightly say I am, yet I cannot explain the searing sensation on my flesh: was the memory forever etched onto my DNA, a pain transmitted temporally through genes and chromosomes?

That is not to say that the scene came as a shock, a sudden fibrillation of a dead valve cultural/social history. One could argue that Jiang Wen builds up to this scene by covering it up with the comedic trope of mis-translation between Chinese and Japanese (languages). The film opens with Da Masan (Jiang Wen) being charged by an unnamed figure, ostensibly a resistance fighter, to safeguard two captured Japanese soldiers until the New Year. It is a task that Da Masan does not undertake with a patriotic fervor, rather he is motivated by the fear of death by the underground resistance force. This undoubtedly places Da Masan and his fellow villagers in a tricky spot. Rack-Armor Terrace is occupied by the Japanese Army, who announced their presence everyday with a bugle call and a routine march through the village. The premise of the film could have lent itself easily to a dramatic mediation of the politics of resistance and collusion among the Chinese during the Japanese occupation, yet Jiang Wen introduces a comedic element through the mis-translations between the two prisoners and the villagers.

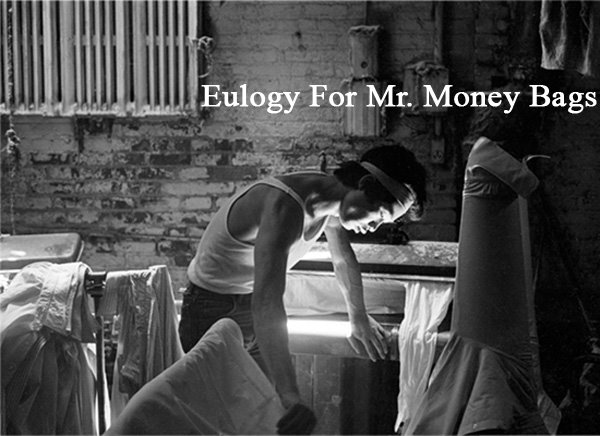

The soldier pictured above on the right is a Japanese by the name of Kosaburo Hanaya (Kagawa Teruyuki). Humiliated by capture, he spits at his captors, cursing the villager’s ancestors in order to goad them into killing him. His insults are defused by his Chinese interpreter, fellow soldier Dong Hanchen figured on the left, who in the name of self-preservation translates the insults and violent physical gestures to the villagers as praises and demonstrations of gratefulness. One notable mis-translation has the villagers laughing as Hanaya’s insult in Chinese, taught to him by Hanchen, translates as prostration through familial identification: “I am your son. You are my dad.” The comedy and laughter that these mis-translations produce is effectively an excess of affect, or sentimentality; it is a laughter during the last of the war and the staccato of bullets.

Jiang Wen’s usage and signification of the sentimentalism or 溫情主義 in “Devil’s on the Doorstep” is vital to our understanding to the film’s reception, which won accolades in film circuits but faced censure in China. It would be useful to utilize Rey Chow’s formulation of the sentimentalism in her analysis of contemporary Chinese films, Sentimental Fabulations: “the sentimental may thus be specified as an inclination or disposition toward making compromises and toward making-do with even – and especially – that which is oppressive and unbearable” (Chow, 18, 2007). Whereas Chow focuses more on domesticity in relation to sentimentality, what I’d like to point out is the sentimentalism, the moderation in excess, found in the laugh, produced by the mis-translations in “Devil’s on the Doorstep”.

Mis-translation in “Devil’s on the Doorstep” functions as a currency of sorts, exchanged between the Japanese and the Chinese in order to maintain the status quo. The Japanese occupiers willingly mis-translate Da Masan’s fear of discovery as simple Chinese excitability and servility. Hanchen mis-translates Hanaya’s outbursts into demands for food and nourishment. The banquet scene, before it instigates the massacre, becomes a jarring tableau of reconciliation and drunken reverie between both the villagers and the Japanese occupiers through an exchange of Chinese and Japanese songs and jokes. Mis-translation effectively allows Da Masan and the villagers of Rack-Armor Terrace to toe the line between patriot and colluder, a middle-road that neither condemns nor explicates Japanese occupation. It takes a position which denies either side precisely because Da Masan and the villagers cannot simply take a side: a reality of the occupied often underlooked.

The massacre scene, the turn of the film, reveals the power dimensions of mis-translation and the status quo. The massacre begins when reconciliation derails because of a mis-translation. Hanaya, now rescued and properly disciplined by the Japanese army, drinks and sings during the banquet. The turn occurs when Hanaya drunkenly screams “I am your son. You are my father” to the Chinese villagers. While the villagers laugh, Hanaya’s superior has the Chinese idiom translated. Enraged by the implications underpinning the idiom, he orders the wholesale massacre of the village, down to the women and children. The overturning of the status quo – ambivalent occupation – occurs on the Japanese army’s terms, reminding us that the status quo, although negotiated and preserved by sentimentalism, ultimately exists on the occupier’s whim.

We have come full circle, back to the massacre, and back to my original question. Where do I place this rage? What identity do I check off in order to legitimate this structure of feeling that bubbles up to the surface with every witnessing? Is there a space in contemporary Asian America for contemporary Asia? Asian American bodies, despite our protestations – Frank Chin immediately comes to mind – continue to be a site for America’s (mis)translations of Asia. If (mis)translation, often from our own mouths, preserves the status quo - the continued formation and canonization of an Asian American identity – we must recognize that this power of representation through (mis)translation resides not with us, but ultimately with the interests at the heart in Amerikka, which was never us to begin with.

No comments:

Post a Comment